Inside AI’s Brain: How Chips Work

By Marsya Amnee & Trason Soh

Previously, we followed the trail behind AI’s growing pains, tracing rising smartphone prices back to data centres and power grids to the hardware accelerators that quietly shape costs. The clues pointed to a system under pressure. Now, it’s time to take a closer look on the brain at the centre of it all.

At first glance, AI feels like instant magic. Type a prompt, get an answer.

But when you look closer, things are not as simple as they seem. Behind every response sits a massive amount of computation, and it all starts with the brain.

In AI, the brain, also known as hardware accelerators, are specialised chips designed to handle the heavy mathematical operations behind AI training and performing inference. These chips process enormous amounts of data in parallel.

Graphics Processing Units (GPUs) dominate today’s AI ecosystem, while custom chips like Tensor Processing Units (TPUs) and Language Processing Units (LPUs) are built for more specialised AI tasks.

From School to the Workforce

A useful way to think of AI training is to compare it to how humans grow up.

As children, we spend years learning. We absorb knowledge, but only later does that learning begin to show its value, when we enter the workforce.

AI pretty much works the same way.

Before it can be useful, an AI model has to be trained. This training phase can take months and consumes enormous computing power (Epoch AI, 2025). Costs pile up, but there’s little direct payoff at this stage. Like education, training is expensive…but necessary.

Once an AI model has gone through training, the real question is this:

How does it deliver answers in real time—quickly and reliably?

Because AI chips don’t just train models, they’re also responsible for inference—the process of generating answers from prompts. This depends on what’s happening inside the AI’s brain at the moment the request comes in. So let’s break down how GPUs retrieve and process data during inference.

GPU, TPU and LPU: Where is Data Stored?

Picture AI running inference like chefs busy preparing cheesecakes for new orders. The bakery kitchen represents the GPU, while high-bandwidth memory (HBM) is the large storeroom next door where ingredients are stored and retrieved.

The storeroom = HBM, where ingredients (data) are kept

The counters, shelves, and clear walkways = bandwidth, allowing ingredients to move quickly and in bulk

The bakery kitchen = the GPU, where all the baking (inference) happens

The chefs and baking stations = the cores that do the work

The chefs first fetch the ingredients they need from the storeroom, carry them across the kitchen, and bring them to their stations, where the actual baking happens.

They can prepare many cheesecakes at the same time, as long as ingredients keep flowing smoothly from the storeroom to the chefs. This setup isn’t unique to GPUs. Other hardware accelerators, such as TPUs, also rely heavily on fetching data from HBM.

But here’s the catch.

When too many chefs are baking at once, they often need the same ingredients simultaneously. Even with wide walkways and counters, chefs start waiting on one another. As orders pile up, movement slows, bottlenecks form, and the kitchen becomes congested.

In short, GPUs rely on a large, shared storeroom that many chefs must access at once. This is why GPUs can experience heavy memory traffic and higher inference latency when generating responses.

But relying on a shared storeroom (HBM) isn’t the only way to prepare an order.

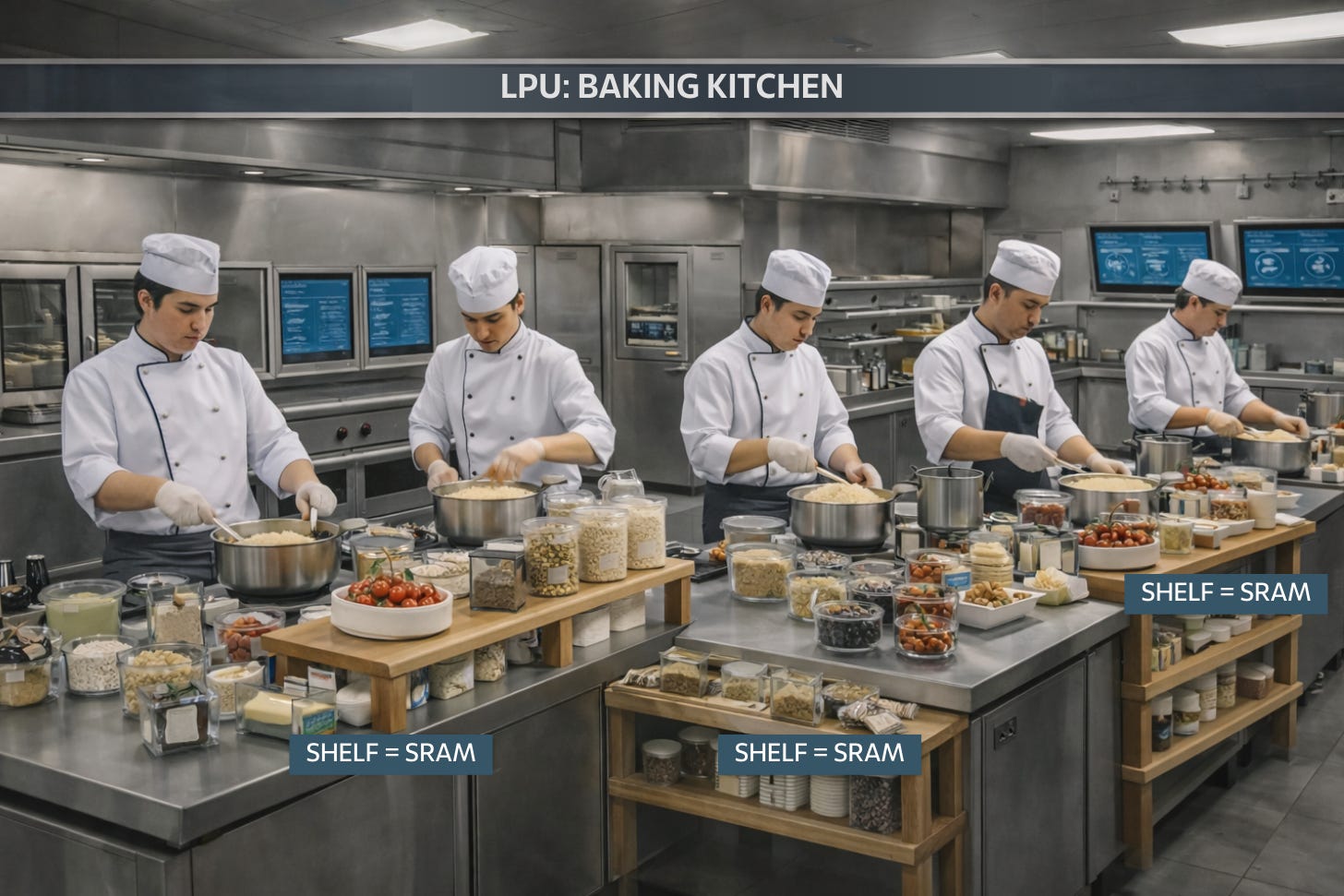

LPU: Ingredients at the Baking Station

Now imagine a different kitchen.

Instead of chefs constantly walking to a shared storeroom, each baking station has its own small shelf of ingredients. This shelf represents SRAM, much smaller than the main storeroom (HBM), but placed right where baking happens.

Because the ingredients are already within arm’s reach, there’s no waiting, no queueing, and no kitchen congestion. Chefs can start baking immediately, resulting in faster and more predictable response times.

This approach has delivered around 2× faster real-time inference in independent tests, which helps explain why LPUs are attracting attention as a complement to GPUs (CNBC, 2025).

The trade-off is capacity.

Each station’s shelf can only hold a limited number of ingredients, so it can’t replace a large shared storeroom. Fitting much more of this fast storage directly into the kitchen remains a major technical challenge (Asia Business Daily, 2026).

Also, LPUs are designed mainly for inference. Training large AI models still depend on GPUs, TPUs and other training-focused hardware.

The Brain Now Needs a Traffic Controller?

As we know by now, AI runs on massive computing power, AI chips aren’t getting any cheaper, supply is tight, and no existing architecture fits every job. As more specialised chips enter the mix, new questions emerge:

How do you decide which chips to use (US or China), how do you get the most out of the chips you already have and what if you want to use chips from both US and China?

Something has to manage the flow of work between them. This is where software steps in.

These traffic controllers decide which jobs run on which chips and when. The goal is to keep expensive AI chips busy doing useful work rather than sitting idle or waiting in line. In practice, this means spreading workloads more evenly and making sure each chip is used for what it does best.

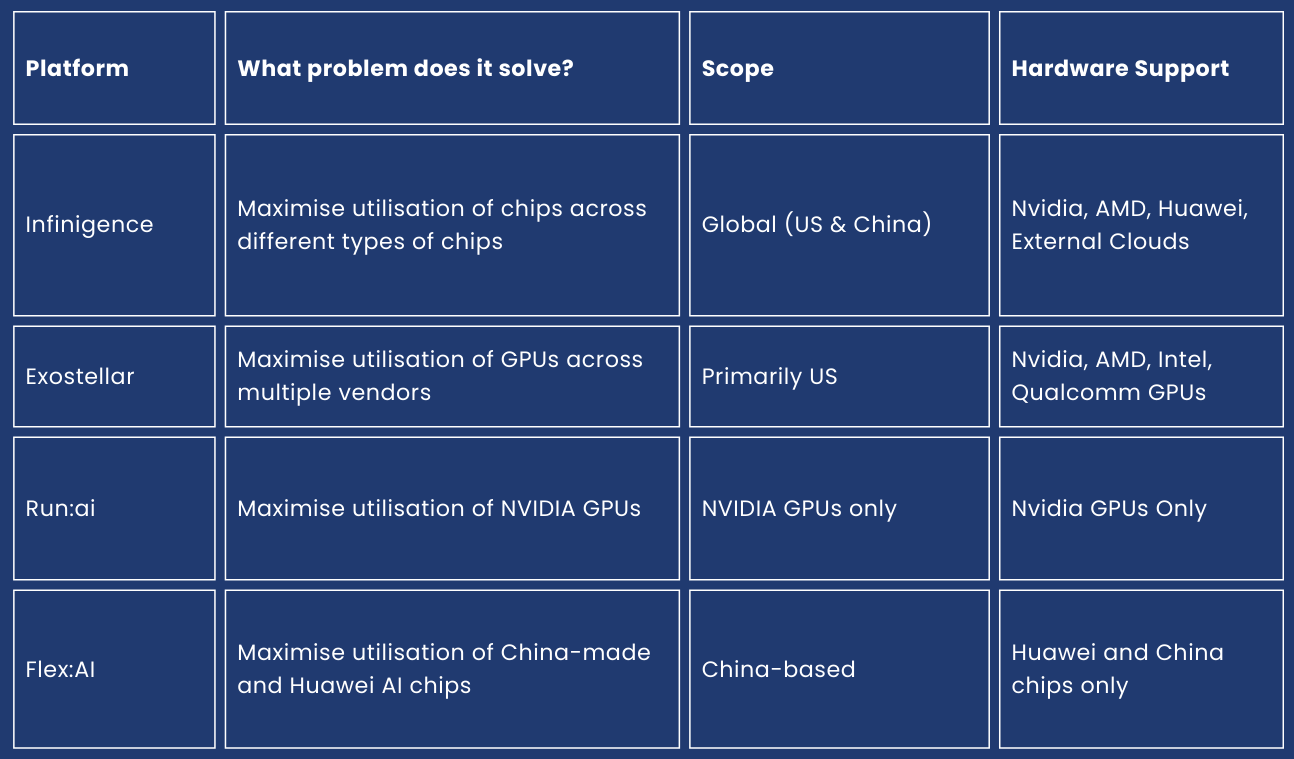

This is where platforms like Infinigence, Exostellar, Run:ai and Flex:AI come in:

Infinigence and Exostellar try to solve a broader problem. Both focus on optimising and coordinating across different chip types from different vendors within the same platform.

Infinigence supports both U.S. and China AI chips, while Exostellar focuses on U.S-based GPU ecosystems.

Meanwhile, Run:ai and Flex:AI, focus on optimising AI chips within a specific hardware ecosystem. Run:ai works best with NVIDIA chips, ensuring that all GPUs are used as efficiently as possible, whereas Flex:AI, developed by Huawei, does a similar job but for Huawei’s Ascend chips and other China-based AI chips.

Where This Leaves Us

AI has moved beyond its early days. The focus is shifting from training models to making inference faster, cheaper and more reliable. Much like the internet, progress was slow and access was expensive, but over time, costs fell and usage scaled. In the next phase of AI, efficiency won’t be a nice-to-have, it will be a competitive advantage.

Coming Up Next

Now that we’ve unpacked the brain behind AI, we turn to where the brain is deployed. We’ll explore more on physical AI — where AI systems are embedded into machines that see, move and act in the real world.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the Sunway iLabs team for their invaluable contribution and insights in preparing this article.

References

Asia Business Daily (2026). Welcome To Zscaler Directory Authentication. Asiae.co.kr. https://cm.asiae.co.kr/en/article/2025123016015748006

Emberson, L. (2025). Frontier training runs will likely stop getting longer by around 2027. Epoch AI. https://epoch.ai/data-insights/longest-training-run

Faber, D. (2025). Nvidia buying AI chip startup Groq’s assets for about $20 billion in its largest deal on record. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2025/12/24/nvidia-buying-ai-chip-startup-groq-for-about-20-billion-biggest-deal.html

FutureX Insights. (2026). Smartphones are Getting Pricier Because of AI?. https://www.futurexinsights.news/p/smartphones-are-getting-pricier-because

Laurent, A. (2025). Nvidia’s $20B Groq Deal: Strategy, LPU Tech & Antitrust. IntuitionLabs. https://intuitionlabs.ai/articles/nvidia-groq-ai-inference-deal