Smartphones are Getting Pricier Because of AI?

By Marsya Amnee

Something’s off. Smartphone prices are inching up again, and the usual excuses don’t fully add up. So what’s really going on?

Recently, word has spread that the AI boom is driving a severe shortage of memory chips, the same components used in both AI data centres and everyday devices like smartphones.

SK Hynix and Samsung, two of the world’s leading suppliers of memory chips, have already sold out their high bandwidth memory (HBM) supply through 2026, with industry expectations that the memory shortfall could stretch into late 2027 (Reuters, 2025). As supply tightens while demand remains red-hot, prices rise. Real inflation pressure.

If artificial intelligence (AI) demand is strong enough to push up prices in everyday tech such as phones and laptops, it tells us something important, that our ChatGPT subscription isn’t getting cheaper anytime soon.

What’s really keeping AI expensive?

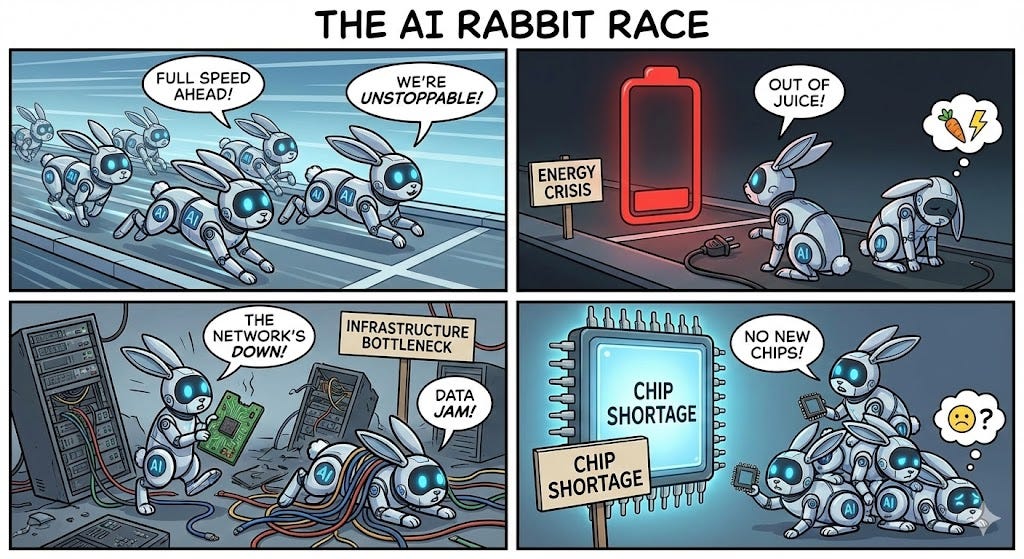

To make sense of it, the Sunway iLabs team stepped back and compared notes, and one thing became clear. This isn’t a single-issue problem. AI needs three main things to work at scale, and all three are under strain. To paint the picture, AI is intelligence with dependencies: it needs a body to carry it, a brain to think and fuel to run it.

Infrastructure: The body that holds everything together

Infrastructure is the body of AI, the physical foundation everything else plugs into. This includes data centres, and those data centres depend on a whole chain beneath them, such as grid connections that deliver electricity, transformers that manage it, and power plants that generate it in the first place. AI chips can’t run without buildings to house them.

One reason AI isn’t getting cheaper is the sheer cost of building this body. Big tech companies are spending hundreds of billions of dollars building AI-ready data centres, so much so that data centre construction is set to overtake office buildings by 2026 (The Wall Street Journal, 2025c). These aren’t ordinary buildings, they require specialised cooling, power distribution, and built-in backups, all of which drive costs higher.

And then there’s time. Even with unlimited funding, data centres and grid connections can’t be built overnight. Physical infrastructure expands slowly, in years rather than months. That heavy, long-build reality puts a natural limit on how fast AI can scale, and helps explain why costs stay high, even as the AI technology itself continues to improve.

Hardware accelerators: The brain doing the thinking

If infrastructure is the body, then hardware accelerators are the brain. AI semiconductors like GPUs and TPUs do the heavy mathematical work behind training and running AI models.

The challenge is that this brain is hard to scale. Most of the world’s AI chips, such as GPUs and TPUs are manufactured by a single company, TSMC. As demand has surged, supply hasn’t been able to keep up, making shortages and pricing pressure hard to avoid.

A major bottleneck isn't just making the chips themselves, but packaging them. AI chips require complex packaging processes that depend on specialised equipment from many vendors and expanding this capacity takes time (Epoch AI, 2024). And because NVIDIA's GPU chips have become the industry standard, many companies are effectively competing for the same limited supply.

Alternatives like Google's TPUs are either tightly controlled, while others such as Huawei's Ascend chips are still catching up (The Wall Street Journal, 2025a). So even as AI software advances quickly, the brain it runs on doesn't scale at the same speed, which helps explain why costs are unlikely to fall meaningfully anytime soon.

Power: The fuel that keeps the lights on

AI doesn’t just think, it consumes. Training AI models takes enormous amounts of electricity, and once those models are deployed, every question asked, image generated, or chatbot reply — known as “inference” — adds to the load. Together, training and usage keep the power meter running almost constantly.

This is where costs start to balloon. Some countries are better positioned than others. In this case, China has a relative edge, with far greater power-generation capacity than the US and cheaper electricity in many regions (The Wall Street Journal, 2025b). The US, by contrast, has strong demand but slower grid expansion, creating congestion and rising costs (Epoch AI, 2024).

At the same time, emerging, fast-growing markets like Malaysia are accelerating data centre expansion precisely because electricity costs are significantly lower than in the US (ACCEPT, 2025).

But here’s the catch: cheaper power doesn’t solve everything. AI remains extremely energy-hungry. Unless AI systems become far more energy efficient, electricity costs alone will keep AI expensive, even in energy-rich countries.

Where this leaves us

When you line up the clues, things start to make sense. AI isn’t expensive just because innovation has stalled. It’s expensive because multiple parts of the system are under strain at the same time.

The most visible constraints are physical: a body that takes years to build, a brain that’s hard to scale, and fuel that keeps burning. Together, they help explain why AI costs remain high. But the physical constraints aren’t the whole story, software, operations and geopolitical conditions matter too.

We’ve seen this pattern before. In the early days of the internet, access was limited, hardware was pricey, and bandwidth felt like a luxury. Over time, as networks expanded and technology matured, costs came down and the internet became accessible everywhere.

AI may follow the same path. But for now, this isn’t a one-bottleneck problem. It’s a system problem.

Coming Up Next

In the upcoming piece, we’ll zoom in on hardware accelerators, the brains behind AI. We’ll take a a closer look at GPUs, TPUs and emerging alternatives like LPUs, explore how these chips differ, where each excels and what their evolution could mean for the future scalability of AI.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the Sunway iLabs team for their invaluable contribution and insights in preparing this article.

References

Huang, R., & Qin, S. (2025a). Huawei Unveils AI Chip Pipeline as Tech Rivalry Heats Up. The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/tech/huawei-unveils-ai-chip-pipeline-as-tech-rivalry-heats-up-07600dc8?mod=article_inline

Huang, R. & Spegele, B. (2025b) China’s AI Power Play: Cheap Electricity From World’s Biggest Grid. The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/tech/china-ai-electricity-data-centers-d2a86935?st=6h2Mq9&reflink=desktopwe…

Jin, H., Potkin, F., Lee, W.-Y., Bridge, A., & Cherney, M. A. (2025). The AI frenzy is driving a memory chip supply crisis. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/china/ai-frenzy-is-driving-new-global-supply-chain-crisis-2025-12-03/

Maurer, M. (2025c). AI Construction Costs Can Be an Accounting “Black Box.” The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/ai-construction-costs-can-be-an-accounting-black-box-3c197b09

Nathania Azalia. (2025). The Rise of Data Centres, Artificial Intelligence, and ASEAN’s Decarbonisation Goal - ASEAN Climate Change and Energy Project (ACCEPT). ASEAN Climate Change and Energy Project (ACCEPT). https://accept.aseanenergy.org/the-rise-of-data-centres-artificial-intelligence-and-aseans-decarbonisation-goal

Sevilla, J. (2024). Can AI Scaling Continue Through 2030? Epoch AI. https://epoch.ai/blog/can-ai-scaling-continue-through-2030